On the Trail of the Founder

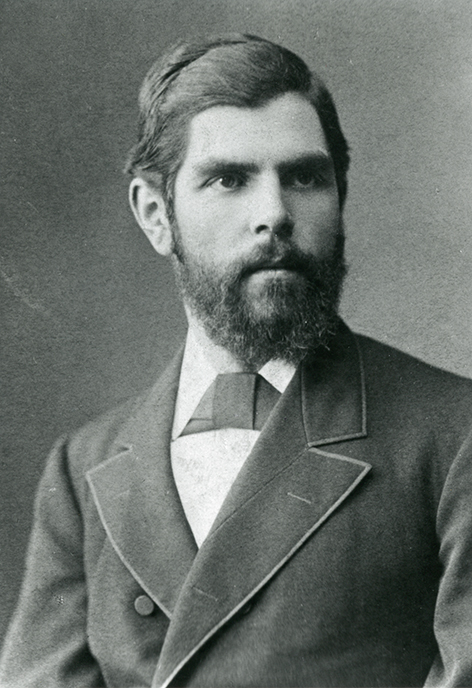

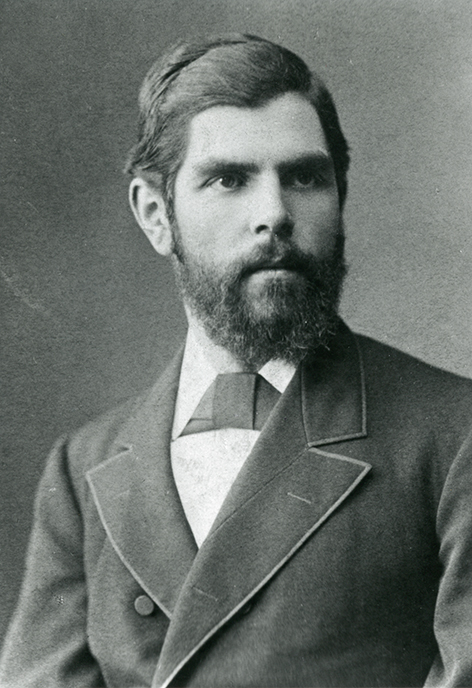

His name is Carl Johann Freudenberg. The success of the technology company bearing his name can be traced back to him. It was 175 years ago – on February 9, 1849 – that he and a partner founded a leather factory in Weinheim. The company’s unique rise followed. Their enterprise would become a global company whose story has been superbly documented in a modern archive as well as other sources. But what does the record tell us about Carl Johann’s personality, about him as a human being? How are his thinking and actions continuing to shape Freudenberg’s corporate values today? The detectives at the Freudenberg Archives are on the case.

“Imagine the founder of a startup who has just become a father for the third time and, in the middle of a revolution, buys a small insolvent business with support from his father-in-law,” suggests Freudenberg Archivist Julia Schneider. Admittedly, this is a simplified image of Carl Johann, but it shows he had no shortage of confidence.

He was fortunate to gather the right elements for a steady, step-by-step rise from apprentice to co-owner, and eventually, the sole proprietor of his own company. What were these elements?

What led him, as a 30-year-old father and family man, to look ahead to success during a time of great uncertainty? “The right character traits are part of the answer. So are the right associations in his business and personal life,” Schneider says.

1829 to 1844

The Child

It all begins with an early, fateful event. Carl Johann was just nine years old when he lost his father, a man who had led a hard life. Georg Wilhelm Freudenberg ran “Zum Löwen,” an inn in Hachenburg, a town between Cologne and Frankfurt. But it was a time of severe poverty in the early industrial era. In early 1829, the inn had to be closed, and its innkeeper had to make a drastic career change.

He found a job at the customs house in Weilburg an der Lahn, but unfortunately, he passed away shortly after.

The date was March 9, 1829. His son Carl Johann had accompanied him from Hachenburg and was the only one with him at the time. His childhood was over. His family mourned and struggled for financial survival. His mother took him and his five siblings to Neuwied, where relatives made sure they would not starve. At 14, Carl Johann was on his own. He began an apprenticeship in his uncle’s leather shop in Mannheim, 200 kilometers (about 124 miles) away. It was a long distance to travel at the time. “The family’s hardship triggered something in Carl Johann and gave him the urge to make something of himself,” Schneider says. “We see this in his later years when he rose to become a kind of self-made man – thanks to his ambition, industriousness and thrift.”

The Up-And-Comer

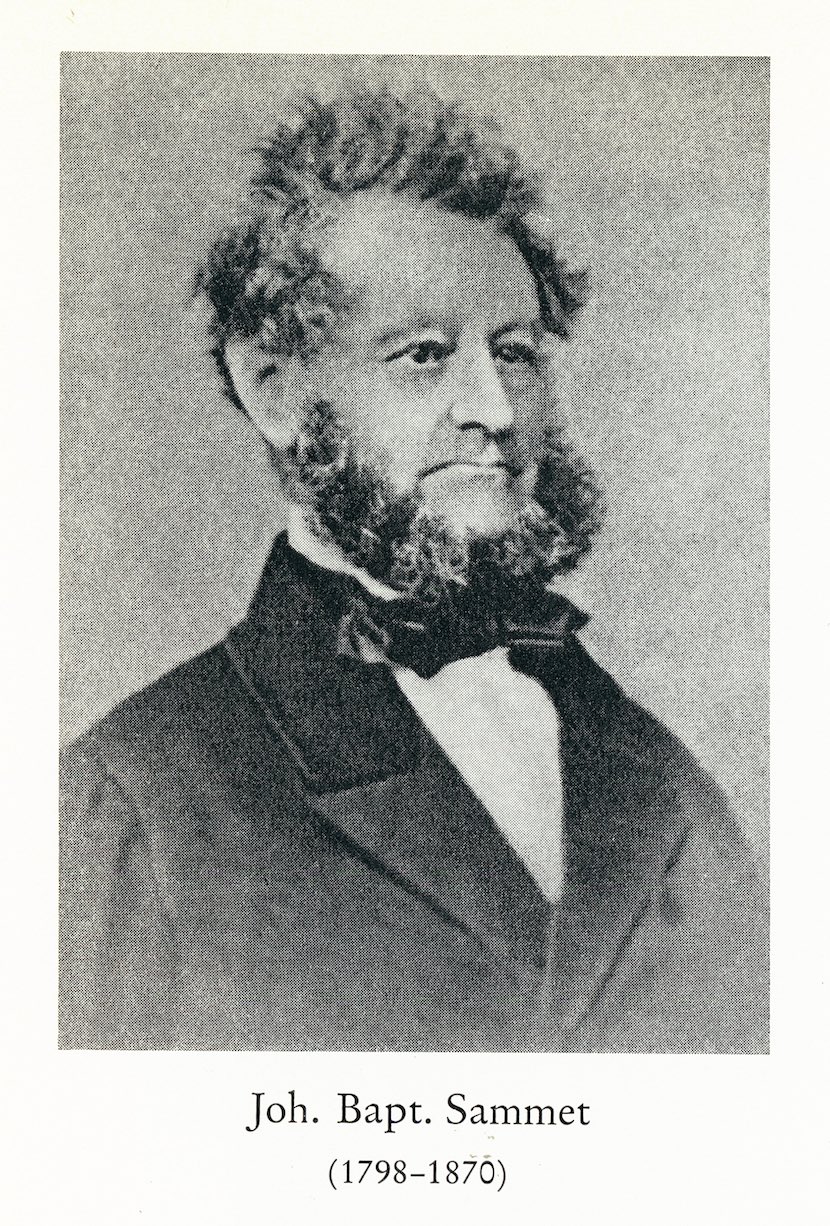

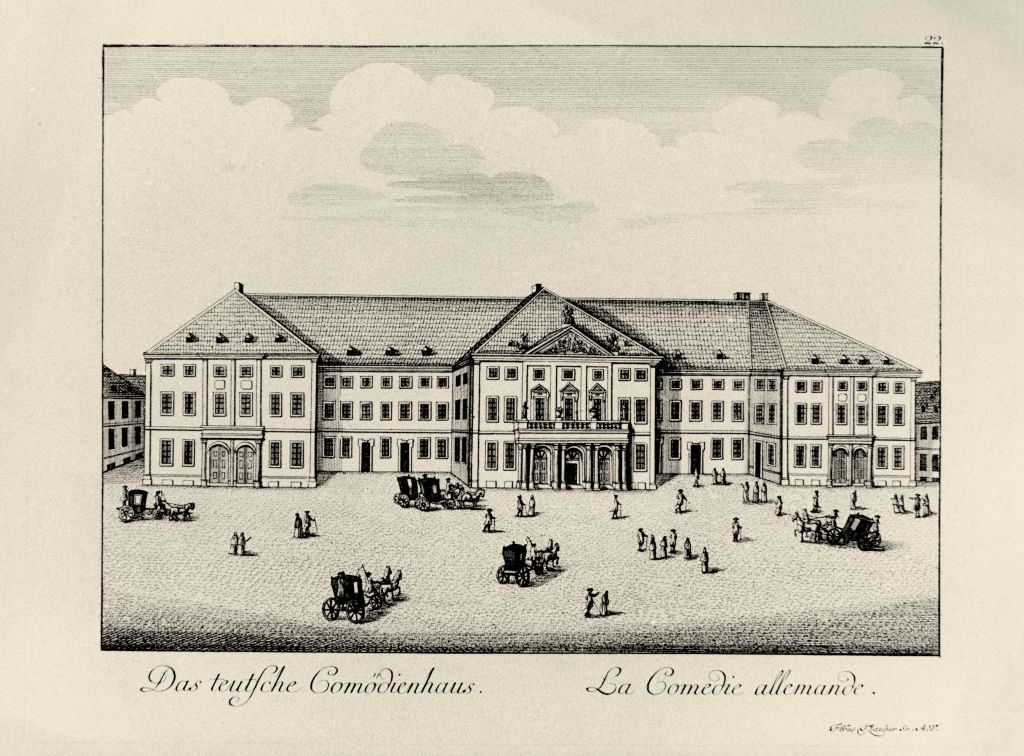

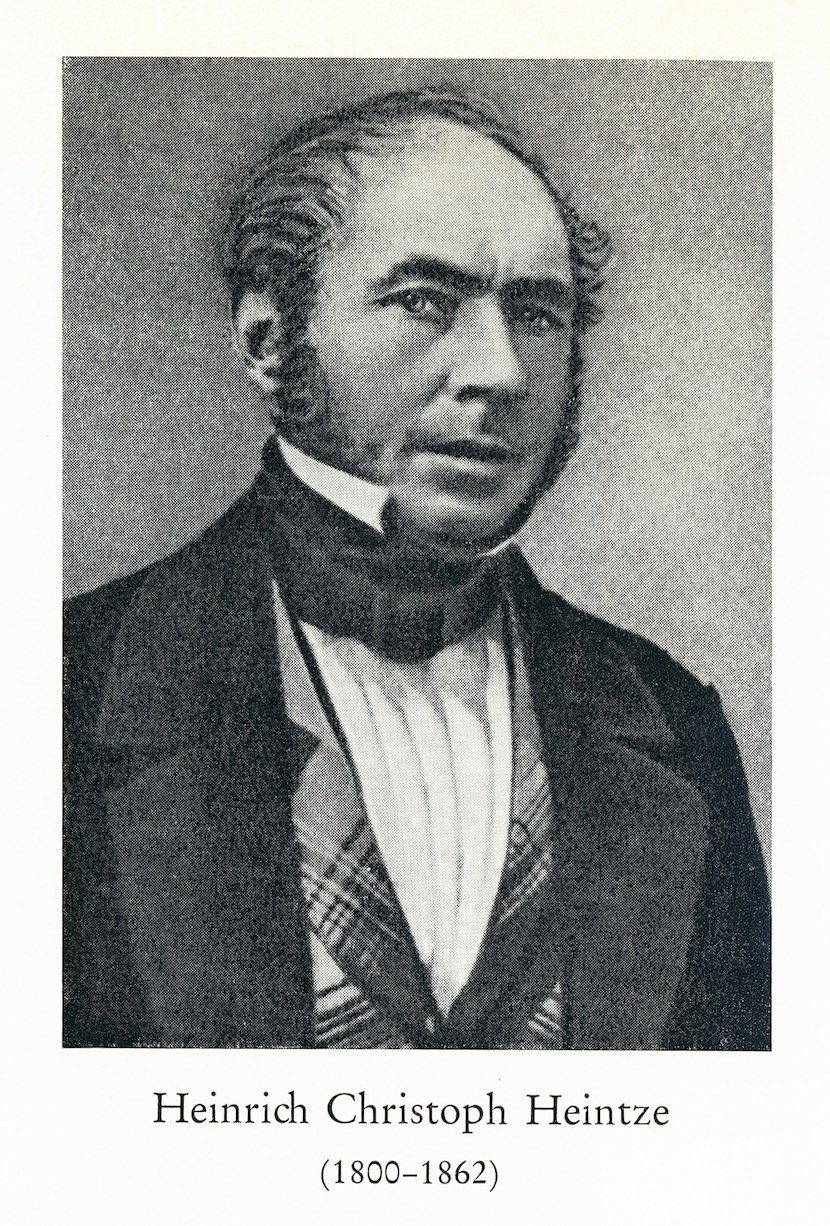

Carl Johann quickly found himself. He discovered his strengths. He supported himself as an apprentice to his uncle, Johann Baptist Sammet, and partner Heinrich Christian Heintze in Mannheim, which was a vibrant, large city and quite a contrast to his hometown. “At this time, he notices the positive impact of his own performance and his own capabilities on his life. This gives him the self-confidence to continue the mission of making something of himself,” Schneider says. His industriousness and ambition drove him on. The young man not only served customers from behind the trading house’s counter and made deliveries – with the help of earnings from the leather business, but he also managed to run a cigar store, improving his finances. Freudenberg, who never attended secondary school, learned French and English. Additionally, he attended the National theater Mannheim where he moved with growing confidence in respected and international circles and continued to shine in his uncle’s company. As a result, in 1844, he was permitted to invest his money into the firm and acquired 20% of its shares as a silent partner.

The Husband

Later the same year: Carl Johann married Sophie Martenstein, whom he had met at a choral event during the spring of the previous year. Martenstein came from a wealthy family from Worms. Her father, a spice merchant, was a respected businessman. He approved the match, but he no doubt looked beyond young Freudenberg’s heart, character and personal appearance in making the decision. There were economic realities to consider, including the suitor’s net worth and his professional success. In her memoirs, Sophie wrote: “The conviction that he was gaining a good, capable son-in-law who had already saved up 5,000 guilders [the equivalent of about €100,000 today], led my father to entrust his only daughter to him.” Children came along over the next few years: The first arrivals were two daughters, Elise and Luise, although the latter died young. When son Friedrich Carl was born in 1848 in Mannheim, the Baden Revolution was already raging.

1848 to 1849

His Contemporaries

What was happening on Carl Johann’s doorstep in Mannheim? At stake was nothing less than press freedom, trial by jury and a German national state with a freely elected parliament. Until that point, the country was a patchwork of independent territories, including the Grand Duchy of Baden, where Mannheim was located. The revolutionaries were divided into two camps, one liberal-constitutional and the other radical-democratic. Disorder reigned in Mannheim. There were calls for radical change. Thousands attended revolutionary peoples’ assemblies, and countless more of them were held across the entire country. There were pitched battles. “Business people who generally want stable political conditions viewed the events anxiously. That was true for our founder as well,” Schneider says. He may have suspected that fate was about to put him to the test – again.

The Entrepreneur

The country was in the throes of political storms. In their midst, the bank that had handled the company’s bills of exchange and financed its leather business collapsed. The firm fell into difficulty and had to be dissolved in 1848. “Let’s return to the concepts of luck and the right ingredients,” Schneider says. “Freudenberg has the good fortune to be able to turn the crisis into an opportunity. He now has a strong family behind him who can give him seed money.” His father-in-law, who thought highly of him, made the capital available to his daughter Sophie so she could help her husband with a plan to acquire part of the company. At the time, it was a progressive notion to involve a daughter in business matters.

Nine decades later, Friedrich Carl, who was born during the year of revolution, wrote in his memoirs: “Since the liquidation required the departure of the two owners, my father was able to choose between them. He chose Mr. Heintze. The firm of Heintze & Freudenberg ended up in Weinheim, taking over the small calf leather tannery in 1849.” Why did he buy into a leather factory with Heintze and not into the leather shop with his uncle? For an entrepreneur, the leather factory had broader opportunities for designs and growth than “just” a leather shop. “This shows Carl Johann’s entrepreneurial vision,” says Schneider. And there was something else: “The conviction that he could pull this off in turbulent times is because he had already extricated himself from a financial crisis as a young man. His personal qualities had made him a success. In a sense, it was a repetition of something that he had already handled. This time, he was determined to use his experience and strengths to his advantage.” Thus, in the middle of a revolution, he set out on a course that would lead to a growing global company. On Friday, February 9, 1849, the partners officially founded the firm of Heintze & Freudenberg with an entry in the commercial registry. The revolution was put down just a few months later.

1850 to 1874

The Head of the Company

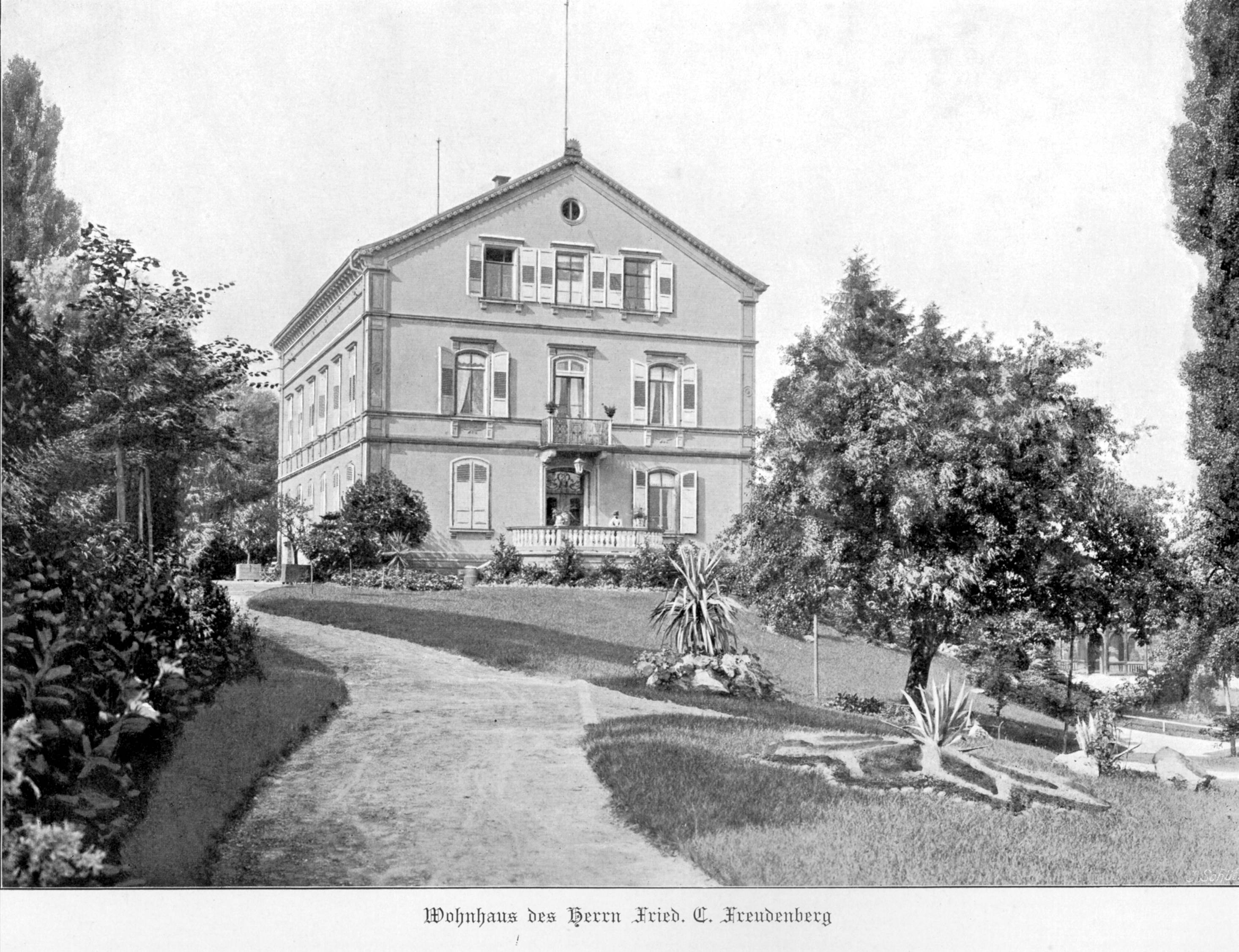

Then things began to move fast. The plan worked out. Over the next three years, revenues quadrupled, and the staff grew from 50 to 170. “Three aspects play an important role here,“ Schneider says. The first is quality. “In Germany alone, there were about 10,000 companies making leather products. Freudenberg knows that he and Heintze are setting themselves apart with quality products.” Secondly, it was clear to him that he had to internationalize the business quickly to buy skins and sell leather. It was either “go big or go down,” as the saying goes. The two businessmen built up relationships in the United States, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, France and Turkey (still the Ottoman Empire at the time.) And finally, Freudenberg recognized the importance of innovation early on, picking up on the patent-leather trend from France and gearing his production operations to it. To make the change, he had to win his partner Heintze over. “If you make patent leather, you get to ride in the carriage. If you make regular leather, you walk,” he once said. He had demonstrated his farsightedness once again. The product from Weinheim was a prizewinner at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 and secured the company’s success for years.

The Mentor

What remains of the spirit of those early years? Or the traits of Carl Johann Freudenberg? After he bought out the Heintze family and the company became a sole proprietorship in 1874 – once again with financial help from his wife’s family – he was able to show his caring side as an entrepreneur. Heintze had been solely interested in cost-efficiency and had presumably stood in the way of his partner’s other interests. That same year, Freudenberg founded a health insurance association for his employees, the forerunner to the health insurance fund that the company later established. A general aid fund followed – it was for employees and their families who were in need. “You can see a connection to his experience as a child,” Schneider says.

True to His Principles

Freudenberg brought his sons Friedrich Carl and Hermann Ernst into the company for support, making it a family operation. In 1887, he made them partners, giving each one-third of the company. At this point, the company had more than 500 employees and substantial obligations for their care. As part of the transition to the next generation and with the size of the company in mind, Carl Johann wrote down his business principles by hand. He considered humility, honesty, a solid financial foundation, and the ability to adapt to change to be the most important principles for a successful business. The theme of trust – not just in oneself but in one’s family, partners, and employees – played a major role. To put it in Carl Johann's own words: “It is better to trust hundred times at risk of being taken in than to mistrust unjustly even once.”

A summary: After misfortunes, Carl Johann Freudenberg always tried “to make the best of any situation,” (as he wrote in his Business Principles) with diligence, thrift, ambition, self-confidence, and adherence to principles. An entrepreneurial vision, the openness to change and the innovation associated with it, and a culture of trust that he personally embraced – these traits made him a successful entrepreneur whose legacy survives in the company culture down to the present.

The principles that he formulated at that time are the basis of the Freudenberg Group’s Business Principles, which are applied worldwide.

175 years of Freudenberg

Family Ties

Freudenberg has been in family ownership for seven generations. And there are entire dynasties of employees, who have worked for the technology company for decades. The following examples illustrate employees’ strong sense of attachment to Freudenberg.

Read more

Discover the world of Freudenberg

We are as diverse as our people, products and applications. Explore the captivating world of Freudenberg.

Read more