Innovations for better lives

How we transform healthcare with cutting-edge technology

Committed to enhancing overall well-being, Freudenberg offers innovative healthcare solutions. From air filters to medical tubing to infant monitoring devices, our products are designed to ensure safety and improve lives. Discover how we are creating a healthier environment with our cutting-edge healthcare technologies.

Minimally invasive and gentle

Better treatment for heart patients

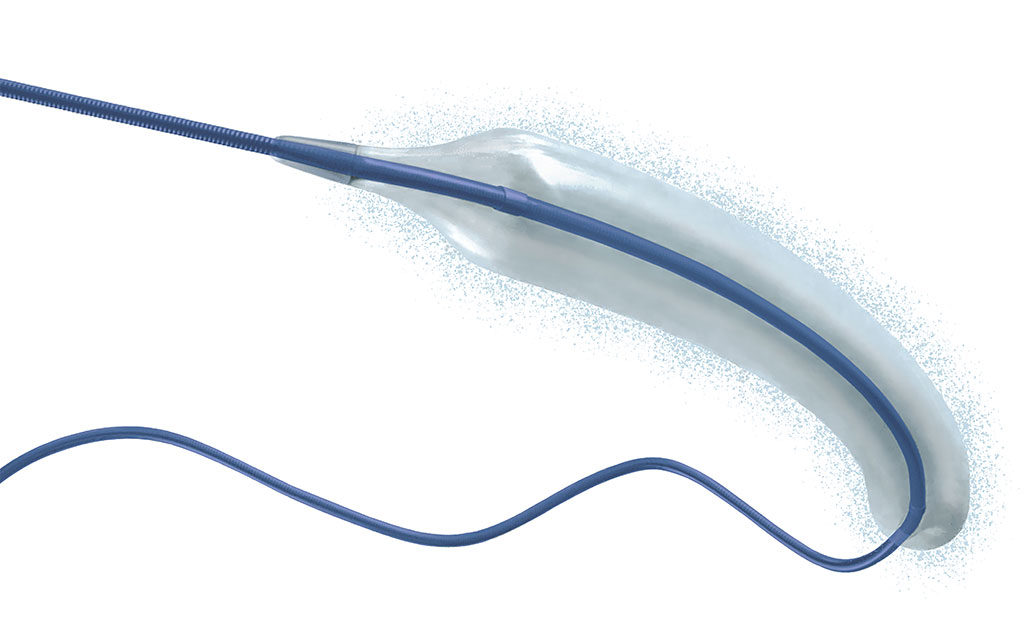

A new medical technology could help millions of heart patients worldwide: Hemoteq, a Freudenberg Medical company, has developed a drug-coated balloon catheter that can keep narrowed heart vessels open over the long term. For this innovation, the team received the “Freudenberg Innovation Award 2025.”

Gentle and effective

Coronary heart disease is the leading single cause of death worldwide. Until now, patients often had to be treated with bypass surgery or stents. The new balloon catheter offers a more gentle alternative:

- Minimally invasive procedure

- No permanent implants (stents)

- Fast recovery and lower risks

Drug-coated balloon catheter

Precision on a micro scale

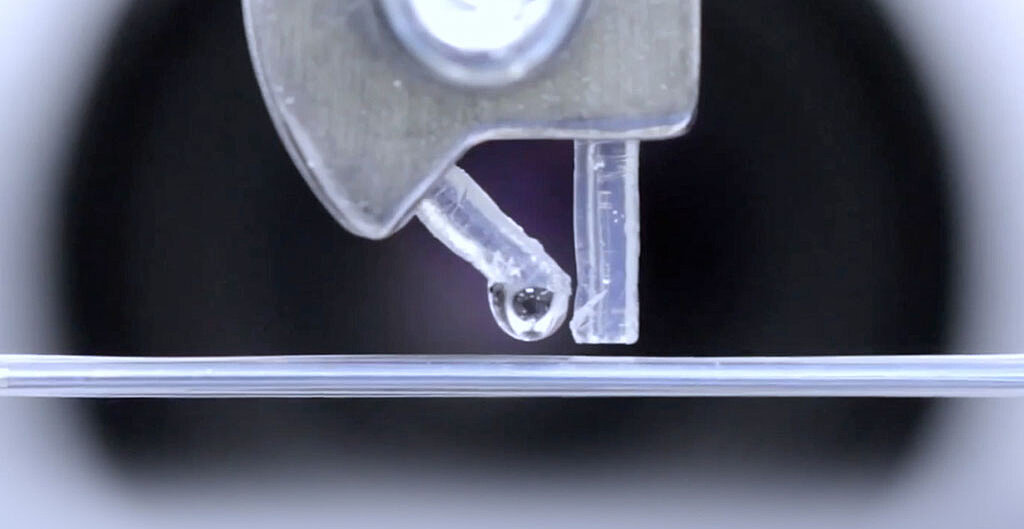

The innovation lies in the special coating: its microcrystalline structure ensures that the drug is delivered precisely and in a controlled way where it is needed.

The balloon is just two millimeters wide and twelve millimeters long – requiring extremely precise manufacturing processes.

Improved quality of life, lower risk

The treatment can be repeated as often as necessary and leads to shorter hospital stays and fewer complications. The balloon catheter is already available in the USA, Europe, and Asia.

Looking ahead

To meet growing demand, Freudenberg Medical is currently building a new 12,000 m² production site in Aachen featuring state-of-the-art cleanroom technology. By 2034, more than 1.1 million patients in the United States alone are expected to benefit from this technology.

Did you know?

Each year, around nine million people die from coronary heart disease due to plaque buildup in the coronary arteries, which restrict blood flow and can lead to heart attacks. Many of these cases could be prevented with timely diagnosis and targeted treatment.

Explore our Business Group

Training device against apnea

The London-based medical technology company Signifier Medical Technologies had the goal of developing a device to treat sleep apnea. Freudenberg made a significant contribution to this. Together with Freudenberg, Signifier Medical Technologies developed a neuromuscular tongue training device.

The device is worn in the mouth for 20 minutes a day and stimulates the tongue muscle with minimal electric shocks, controlled via a smartphone app. The mouthpiece is manufactured by Freudenberg in Kaiserslautern.

The material used in the device is an electrically conductive silicone that Freudenberg developed especially for Signifier Medical Technologies.

biocompatible release agents boost efficiency & improve quality

Medical development has never progressed so fast. With more and more patients receiving cutting-edge care, the rising expenses must be countered. Chem-Trend’s release agents help manufacturers of medical equipment boost efficiency, generate lower expenses, and improve quality. Collaborating closely with customers to solve the most difficult production challenges, Chem-Trend plays a vital role - one that makes a difference to manufacturers and patients alike.

We help our customers to make their operations more sustainable

Chem-Trend release agents play a vital role in many manufacturing processes - helping to enhance productivity, prolong the lifespan of tools and molds, accelerate production, and reduce defect rates. Thereby they do not only increase productivity and profitability, but our technology also helps manufacturers to make their production more sustainable.

Our close collaboration with the medical sector and other industries leads to custom-made innovations that improve manufacturing production at a variety of levels.

Since Chem-Trend developed the first water-based die lubricant in the 1960s, the company has invested extensive resources to continuously innovate and become a world leader in release agent systems and solutions and a trusted partner for manufacturers in a broad range of industries.